Glam rock

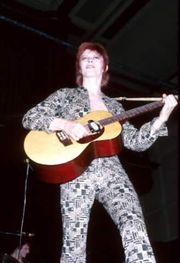

Glam rock (also known as glitter rock) is a style of rock and pop music that developed in the UK in the early 1970s, which was performed by singers and musicians who wore outrageous clothes, makeup and hairstyles, particularly platform-soled boots and glitter.[1] The flamboyant costumes and visual styles of glam performers were often camp or androgynous, and have been connected with new views of gender roles. Glam rock visuals peaked during the mid 1970s with artists including David Bowie, T. Rex, Roxy Music and Gary Glitter in the UK and New York Dolls, Lou Reed and Jobriath in the US.

History

Glam rock emerged out of the English psychedelic and art rock scenes of the late 1960s and can be seen as both an extension of, and reaction against, those trends.[2] Musically it was very diverse, varying between the simple rock and roll revivalism of figures like Alvin Stardust to the complex art rock of Roxy Music, and can be seen as much as a fashion as a musical sub-genre.[2] Visually it was a mesh of various styles, ranging from 1930s Hollywood glamor, through 1950s pin-up sex appeal, pre-war Cabaret theatrics, Victorian literary and symbolist styles, science fiction, to ancient and occult mysticism and mythology; manifesting itself in outrageous clothes, makeup, hairstyles, and platform-soled boots.[3] Glam is most noted for its sexual and gender ambiguity and representations of androgyny, beside extensive use of theatrics.[4] It was prefigured by the showmanship and gender identity manipulation of American acts such as The Cockettes and Alice Cooper.[5]

The origins of glam rock are associated with Marc Bolan, who had renamed his folk duo to T. Rex and taken up electric instruments by the end of the 1960s. Often cited as the moment of inception is his appearance on the UK TV programme Top of the Pops in December 1970 wearing glitter, to perform what would be his first #1 single "Ride a White Swan".[6] From 1971, already a minor star, David Bowie developed his Ziggy Stardust persona, incorporating elements of professional make up, mime and performance into his act.[7] These performers were soon followed in the style by acts including Roxy Music, Sweet, Slade, Mott the Hoople, Mud and Alvin Stardust.[7] While highly successful in the single charts in the UK, very few of these musicians were able to make a serious impact in the United States; Bowie was the major exception becoming an international superstar and prompting the adoption of glam styles among acts like Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, New York Dolls and Jobriath, often known as "glitter rock" and with a darker lyrical content than their British counterparts.[8]

In the UK the term glitter rock was most often used to refer to the extreme version of glam pursued by Gary Glitter and his support musicians the Glitter Band, who between them achieved eighteen top ten singles in the UK between 1972 and 1976.[9] A second wave of glam rock acts, including Suzi Quatro, Roy Wood's Wizzard and Sparks, dominated the British single charts from about 1974 to 1976.[7] Quatro directly inspired the pioneering Los Angeles based all-girl group The Runaways.[10] Existing acts, some not usually not considered central to the genre, also adopted glam styles, including Rod Stewart, Elton John, Queen and, for a time, even the Rolling Stones.[7] Punk rock helped end the fashion for glam from about 1976.[8]

Subsequent influence

Although glam rock went into a steep decline in popularity in the second half of the 1970s it was a direct influence on acts that rose to prominence later, including Kiss and American glam metal acts like Quiet Riot, W.A.S.P., Twisted Sister and Mötley Crüe.[11] It was a major influence on the New Romantics in Britain, acts like Adam Ant and Flock of Seagulls extended it, and its androgyny and sexual politics were picked up by acts including Culture Club, Bronski Beat and Frankie Goes to Hollywood.[12] It also had a less direct influence on the formation of gothic rock, which picked up on the make-up, clothes and theatricality and even on punk rock, which adopted some of the performance and persona-creating tendencies of the genre.[8] In Japan in the 1990s, visual kei was strongly influenced by glam rock aesthetics.[13] Glam has since enjoyed continued influence and sporadic modest revivals in R&B crossover act Prince,[14] and bands such as Placebo,[15] Chainsaw Kittens and The Darkness.[16]

Film

Some examples of movies that reflect glam rock aesthetics include:

Further reading

- Philip Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2006 ISBN 0472068687

- Rock, Mick, Glam! An Eyewitness Account Omnibus Press, 2005 ISBN 1.84609.149.7

See also

- Glam punk

- List of glam rock artists

References

- ↑ "Glam Rock". Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. http://www.webcitation.org/query?id=1257013401672884. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 R. Shuker, Popular Music: the Key Concepts (Abingdon: Routledge, 2nd edn., 2005), ISBN 0-415-34770-X, pp. 124-5.

- ↑ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, pp. 57, 63, 87 and 141.

- ↑ "Glam rock", Allmusic, retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ↑ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0472068687, p. 34.

- ↑ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0472068687, p. 196.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 P. Auslander, "Watch that man David Bowie: Hammersmith Odeon, London, July 3, 1973" in I. Inglis, ed., Performance and Popular Music: History, Place and Time (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, p. 72.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 P. Auslander, "Watch that man David Bowie: Hammersmith Odeon, London, July 3, 1973" in Ian Inglis, ed., Performance and Popular Music: History, Place and Time (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, p. 80.

- ↑ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, p. 466.

- ↑ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, pp. 222-3.

- ↑ R. Moore, Sells Like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Culture, and Social Crisis (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2009), ISBN 0814757480, p. 105.

- ↑ P. Auslander, "Watch that man David Bowie: Hammersmith Odeon, London, July 3, 1973" in I. Inglis, ed., Performance and Popular Music: History, Place and Time (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, p. 79.

- ↑ I. Condry, Hip-hop Japan: Rap and the Paths of Cultural Globalization (Duke University Press, 2006), ISBN 0822338920, p. 28.

- ↑ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, p. 227.

- ↑ P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock (London: Rough Guides, 3rd edn., 2003), ISBN 1843531054, p. 796.

- ↑ R. Huq, Beyond Subculture: Pop, Youth and Identity in a Postcolonial World (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), ISBN 0415278155, p. 161.

- ↑ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, p. 81.

- ↑ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, p. 55.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, p. 63.

- ↑ International Who's Who in Popular Music 2002 Europa International Who's Who in Popular Music (Abingdon: Routledge, 4th edn., 2002), ISBN 1857431618, p. 194.

- ↑ "On The Film Programme this week". The Film Programme. BBC Radio 4. 06 April 2007. http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/arts/filmprogramme/filmprogramme_20070406.shtml. Retrieved 12 February 2010..

- ↑ L. Hunt, British Low Culture: From Safari suits to Sexploitation (Abdindon: Routledge, 1998), ISBN 0415151821, p. 163.

- ↑ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0754640574, p. 228.

- ↑ L. C. Cahir, Literature into Film: Theory and Practical Approaches (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2006), ISBN 0786425970, p. 181.

- ↑ M. Pramaggiore, Neil Jordan: Contemporary film directors (Chicago IL: University of Illinois Press, 2008), ISBN 0252075307, p. 123.

External links

|

Pop music |

|

| By style |

|

|

| By region/country |

American · Arabic · Balkan · Canada · Chinese ( Cantopop · Mandopop) · HK English · Europop (Austropop, French, Nederpop, Swedish) · Greek · Indian (Filmi) · Japanese ( Picopop, Shibuya-kei) · Korean · Laotian · Latin (Brazilian · Mexican) · Pakistani · Persian · Philippine · Russian · Ukraine · SFR Yugoslavia · Taiwanese · Thai · Turkish · United Kingdom |

|

| Other topics |

|

|

|

Pop rock |

|

|

|

|

| See also: The Rock music portal |

|

|

Rock music |

|

|

|

|

| Other topics |

|

|

| See also: The Rock music portal |

|